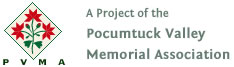

The Deerfield/Pocumtuck area circa 1550, by Will Sillin

Old Deerfield Village Historic Landmark District- The Pocumtuck Fort and its surrounding fertile fields, cultivated by Wôbanaki Pocumtuck and their ancestors from time immemorial, were an important homesite within the Pocumtuck homeland. These fields are bounded by the Deerfield (originally Pocumtuck) River to the west and the Pocumtuck ridge to the east. The river and ridge figure prominently in Native “deep-time” stories.

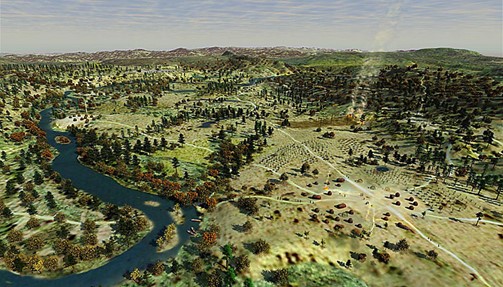

The landscape and its history connect us viscerally to the differing beliefs over land that drove disputes between Indigenous peoples and European colonists. Five thousand acres of the original land grant of the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to a group of English proprietors in Dedham, Massachusetts, were superimposed on Pocumtuck homelands and the Deerfield Landmark District still bears the recognizable imprint of the original 17th century common field system introduced by the first English settlers. A partial map of the villages houselots and fields in 1671 still survives and is shown below.

PVMA digital collections

The steep incline in the village center underscores the strategic location of the first English fortified settlement planted upon a pre-existing Pocumtuck village site. The wooded slopes of the Pocumtuck ridge offer visual reminders of its importance for woodlots and fresh water for its inhabitants, past and present. Within the Landmark District are restored colonial houses and exhibit spaces. Indigenous and European archaeological sites in this region, including the Pocumtuck Fort on the ridge above the village of Deerfield, provide tangible evidence of international alliances and trade as well as conflict among First Peoples and Europeans. Staff and scholar-led walks throughout the workshop connect teachers first-hand with workshop themes as they traverse this contested landscape and are immersed in an historically evocative setting.

Mount Sugarloaf, South Deerfield, Massachusetts.

Mount Sugarloaf- A trip to Mount Sugarloaf will help Summer Scholars to situate themselves geographically and chronologically. At this elevation (1,000 feet), one can identify physical features while imaginatively populating the landscape as it appeared at the turn of the 18th century. Looking down the valley one can picture small English settlements nestled by the river on the ancestral Wôbanaki (Abenaki) homelands, supported by some of the most fertile soil in the world. The view to the north includes the site of the Pocumtuck Fort where a generation of Pocumtuck people planted, fished, and gathered, and where they processed metal and other trade goods acquired from European newcomers- Dutch, English and French.

Mount Sugarloaf, or Wequamps, is the central image of the Wôbanaki Pocumtuck story of the “Amiskwôlowôkoiak”- the people of the beaver-tail hill. Taking advantage of this opportunity to model experiential, site-based learning, we will explore this “deep-time” story as an example of the ways in which Indigenous stories in this genre describe in metaphorical terms how ancient geological events reshaped the landscape, forming mountains, rivers, lakes, islands, and rocky outcroppings. We will also discuss how oral narratives about the landscape formed part of a larger body of knowledge that enabled Native people to efficiently hunt, fish, gather and plant, make climate predictions, and situate homesites in the best locations.

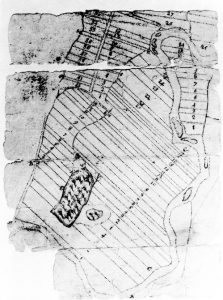

Rock Dam, Connecticut River Turners Falls, MA Antique Postcard

Peskeompskut- Summer Scholars will tour Peskeompskut and nearby Wissatinnewag, an ancient Pocumtuck encampment. For generations Peskeompskut (now Turners Falls, Massachusetts) was a gathering place where Indigenous people from a variety of nations fished at a large waterfall on the Connecticut River. In 1676, during Metacom’s (King Philip’s) War, they suffered devastation in a pre-dawn attack on the site and suffered the loss of 300 elders, women, and children. At Wissatinnewag teachers will traverse the rugged landscape along a deep ravine on a trail believed to be an original pathway used by Indigenous peoples, and view highlights of the area as they learn what the site reveals about Pocumtuck life in this time.

Fort at No. 4 at Charlestown, New Hampshire. Photograph by Lynne Manring.

The Fort at No. 4- Located one hour north of Deerfield, the Fort at No. 4 was one of a line of forts constructed to defend English settlements from attack by the French and their First Nations allies in the decades following the raid on Deerfield. The Fort at No. 4 staff will discuss the reconstruction of an early 18th-century fort based on documentary and surviving archaeological evidence, the frontier experience of civilians living in a fortified community in the mid-1700’s, as well as strategies for using historical sites to gain a deeper understanding of the people and events of the colonial period.